Reward Strategy

Reform of Executive Reward – How Much is Too Much (or Not Enough)?

PARC will be hosting an important members’ discussion on the Reform of Executive Reward on 19 June. For many years, the debate on this critical topic has arguably been random and confused. The purpose of this event will therefore be to create a tighter consensus on what ‘reform’ is actually needed and the best way of going about that reform.

We will aim to get behind some of the questions arising from this debate and to focus on practical solutions to:

- Understanding and managing the predominant ‘narrative’

- Recognising and responding to specific challenges

- Understanding the resulting barriers to business performance and how these might best be addressed.

To set the scene, this blog looks at how some of the randomness and confusion has arisen. Much of what we discuss below is not likely to change in the near future. It forms the backdrop to the Reward professional’s environment. At the event, we will get into more detail about how we manage within these constraints and deal with the often conflicting arguments.

“Something must be done about senior executive pay”. At least, that’s what banner headlines have been telling us for decades. Beyond the headlines, though, there seems to be no clear consensus about the specific nature of the problems that need to be addressed. Articles on the subject, even in publications where we might expect journalists to be well-informed, frequently confuse actual pay received with (often remote and unlikely) potential future earnings. This is usually the fault of the ‘total pay’ figure that companies are required to provide. Arguments about the wider social and economic impacts of high pay are similarly confused and data lite.

The arguments for reform fall into three broad (and sometimes overlapping) areas:

- Executive pay in the UK is too high – it is socially divisive and is fuelling inequality.

- Executive pay in the UK is too low so companies are losing key talent to higher paying countries.

- Executive pay is rewarding the wrong things (or is rewarding failure).

Executive reward is too high and fuels inequality

The first of these arguments tends to take most of the column inches. In the UK, the term ‘fat cat bosses’ became lodged in the public consciousness in the early 1990s, after newspapers published the pay of executives in the recently privatised utilities. It has reappeared at various points over the last three decades. The High Pay Centre thinktank, set up in 2009 to monitor senior executive pay, marks ‘fat cat day’ each year. This is the date, usually sometime in January, on which it calculates that the earnings for the average FTSE 100 Chief Executive surpasses the amount that the average UK worker can expect to earn all year. Its report in December 2023 noted that the median ratio of chief executive’ pay to that of the median UK employee was rising after a ‘moment of solidarity’ during the pandemic, when pay gaps narrowed.

Yet the reasons why critics believe high executive pay is a bad thing are less easy to discern. Rising inequality and the social and political problems it brings with it are often cited as reasons why people should be concerned about high executive pay. However, the argument that executive pay has contributed significantly to rising inequality is not born out by the evidence. As the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) noted:

“Highly paid executives, such as CEOs, receive much attention in the popular press, but they are not a majority of top earners.”

The total remuneration paid to CEOs of the UK’s 100 largest public companies accounts for around 1.2% of the earnings of the top 0.1%.

Across most advanced economies, increases in income inequality since the 1980s have been primarily driven by increases in pay differences between firms in different sectors. In other words, income inequality has been driven by certain well-paid sectors, such as financial services, pulling away from the others. As the IFS pointed out:

“The top of the income distribution seems increasingly populated not by the most senior individuals from a wide range of firms, but by the employees of a narrower group of high-paying companies concentrated in, for example, the finance industry.”

Furthermore, the reporting on executive reward levels is often sensationalist, even in the ‘quality’ newspapers. For example, you have to read some way down from the FT headline about the Boeing CEO’s $33m pay to discover that his actual take-home in 2023 was $5m and his share options are currently worthless due to the collapsing share price.

There is also some evidence that outrage over high pay is driven not so much by rising inequality as by economic downturns. As Mercer’s Peter Boreham remarked:

“Fewer people worried about executive pay when everybody’s living standards were rising. In 2008 the music stopped! Bankers’ bonuses and senior pay became a focus of outrage. This was a major reset for reward. It introduced a new concept of fairness. Fair pay for senior executives became seen as being relative to the rest of the workforce.”

The initial ’fat cat’ outrage of the early 1990s came in the context of an economic downturn and the unpopularity of the Conservative government, which provided ideal conditions for a media campaign and the weaponisation of senior executive pay by opposition politicians. The row formed the backdrop to the corporate governance reforms of the 1990s which led to the creation of Remuneration Committees. However, while they might have changed the process of managing executive reward in UK companies, these reforms did little to dampen the criticism of executive pay.

Executive reward is too low – the UK is becoming uncompetitive

The counter argument to pay being too high is that UK executive pay is too low and is in danger of making the country uncompetitive in the global pay market. The intervention by London Stock Exchange CEO Julia Hogget in 2023, criticising opposition to pay increases even when senior executives’ pay levels were below global benchmarks, attracted significant support. Smith & Nephew Chair Rupert Soames coined the term BRILO (British In Listing Only) to describe those companies listed in the UK but doing most of their business elsewhere in the world. For these organisations, he argued, “The current position on pay is not actually sustainable.” Their executives based in the US need to be paid in line with the reward packages of the US listed companies with whom they compete for talent.

Julia Hogget warned that the UK is in danger of exporting “skills, talent, tax revenue and the companies that generate it”. Over the past year, there have been some high profile defections to the US by companies listed in the UK, such as betting group Flutter, building supply firm CRH, packaging company Smurfit Kappa and plumbing equipment supplier Ferguson.

Smith & Nephew’s proposed pay increase for its CEO narrowly passed, despite a 43% vote against, and strong opposition from proxy adviser Institutional Shareholder Services. On the other side, Glass Lewis supported the proposal saying that Smith & Nephew had given a “compelling rationale” for paying more to its US-based executives.

Is this the sign of a shift in the mood music on executive pay? The Guardian’s Nils Pratley seems to think so. Pointing to other significant shareholder-approved remuneration increases, at London Stock Exchange Group and Astra Zeneca, he declared, “At 3-0 to the Brilos, the boardroom pay game has changed for ever.” The Irish Times agreed, saying that “US-style packages have arrived in Europe”.

Research by Deloitte indicates that there may be something in this. As its executive reward partner Mitul Shah told the FT:

“We are seeing an increase in large, global FTSE 100 companies moving forward with more radical pay proposals this year, both in terms of incentive levels and the structure of pay.”

However, it is likely that public and investor opposition will remain for some time.

Calling a change in the mood might be premature. Media outrage and investor pushback against ‘excessive’ executive reward packages is likely to be a feature for some time yet.

Executive pay is rewarding the wrong things

‘Rewards for Failure’ is a phrase almost as common as ‘Fat Cats’ when it comes to reporting on executive pay. It was even used as the title of a House of Commons report on the subject.

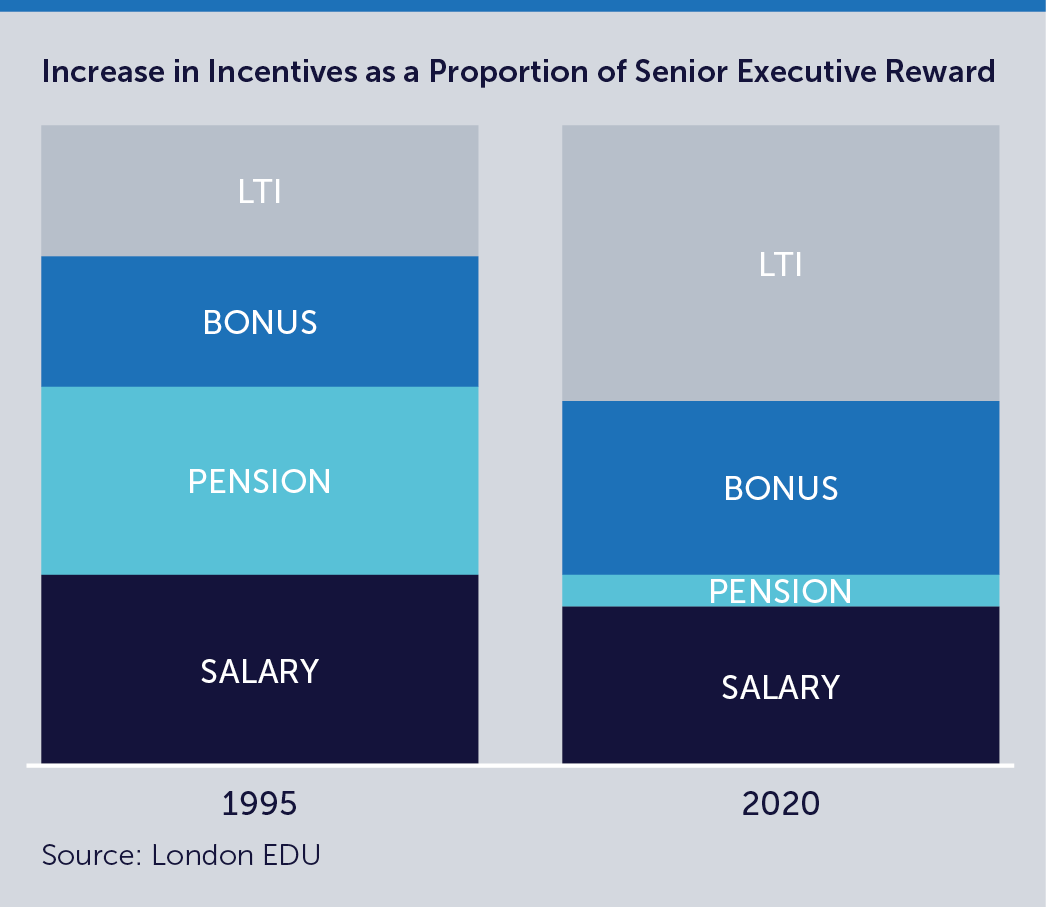

In theory, the situation should be improving. As Tom Gosling of London Business School pointed out in the PARC Performance Measurement Trilogy, the proportion of executive pay determined by performance-related measures has increased significantly in the last two decades.

However, commenting on this at the same event, George Feiger, Executive Dean of Aston Business School, noted that the rise in the ratio of CEO earnings relative to the rest of the workforce had not been accompanied by a corresponding increase in productivity in the UK economy. If the economy is flatlining while CEO pay is still rising at a brisk pace, one might wonder what the country’s CEOs have been up to.

One of our conclusions from PARC’s Performance Measurement Trilogy was that defining and measuring organisational performance is becoming increasingly difficult as the understanding of what constitutes ‘good corporate governance’ has broadened to include a wider set of stakeholders, including responsibilities to the wider public and environment. Defining the difference between success and failure was fiendishly complex even when there were only the potentially conflicting interests of shareholders and executives to balance. Adding in the challenges of environmental and social measurements, becoming more salient as concern over climate change rises, brings still more dimensions to the discussion and therefore more scope for challenges.

All the more reason, then, that companies need to communicate the reasoning behind their executive pay proposals. In PARC’s Reward Manifesto and Future Reward Skills reports we emphasised the need for Reward leaders to develop a well-structured strategic response to these challenges. Many of the responses to Reward proposals may appear ill-informed – and even somewhat hysterical – but most are fairly predictable. Anticipating these challenges, discussing the arguments with those who make them, and being able to develop a well-crafted response are crucial skills for the Reward professional.

It is no coincidence then that outrage about executive pay peaked during the 1990s recession, again during the aftermath of the 2008 Financial crisis. and then again during the current cost-of-living crisis. When it comes to criticism of executive pay, perceived increases in inequality are less relevant than squeezes on people’s overall living standards. The pay of senior executives in quoted companies has become a lightning rod for general economic discontent.

Capitalism’s promise has always been that the pie is growing for everybody. If the pie stops growing, zero-sum thinking about pay (one person’s pay rise is at the expense of another person’s pay cut) becomes more likely. Given the UK’s prolonged economic stagnation and slow growth forecasts, it is likely that the media focus on ‘excessive pay’ will be a feature of the political landscape for some time to come.

Blaming the media and poor reporting is rarely an effective response in any line of work. More important is to focus communication on any misleading aspects of the prevailing ‘narrative’ – and on addressing the legitimate problems and issues. It is highly likely that executive pay will continue to be labelled ‘excessive’ and that calls for ‘reform’ will continue for some time to come. They simply constitute a ‘feature’ of the Reward professional’s job.

UPCOMING CRF CONFERENCE:

UPCOMING PARC EVENT

Reform of Executive Reward

Wednesday 19 June, In-Person, London