Business Strategy

Industrial Strategy in the 21st Century – Preparing Business for the New Economy

Industrial Strategy is back. Having been a rarely-used term for the last thirty years, due to scepticism around ‘government intervention’, suddenly the OECD, the IMF and the World Bank – as well as most major global economies are discussing it as a means of tackling global economic stagnation – and it is all over the business pages.

Our PARC event on 22 February 2024 will take a detailed look at how major global economies are shaping their Industrial Strategies, and what that might mean for business. We will draw on the expert knowledge of Giles Wilkes, partner at Flint Global and former adviser on Industrial Strategy to Number 10, and economist Vicky Pryce, as well as the insight of member companies, to provide greater insight into the global picture and the likely direction of travel.

Four factors have combined to push Industrial Strategy back up the agenda:

- A global pandemic which showed up the fragility and interdependency of supply chains.

- Geopolitical volatility, including wars in Europe and the Middle East that have split the world.

- The synchronised stagnation of the advanced economies after 2008, that looks set to persist well into the 2020s.

- Increasing climate events and the looming urgency of moving to Net Zero.

In recent decades, governments didn’t worry about their access to crucial materials and even ran down their stockpiles, confident in the ability of the globalised market to provide – as Ed Conway detailed in his new book, Material World. Now businesses and governments want security of supply. ‘Just In Case’ has trumped ‘Just In Time’. Doing more at home and buying more from close allies underpins investment and growth.

The Biden administration made a start in 2022, putting hundreds of billions of dollars into the development of domestic green technology, accelerating the shift to Net Zero, reducing dependence on foreign energy, and boosting the sustainability of the American economy.

The EU responded with its Green Deal Industrial Plan, loosening its state aid rules to allow European Commission and state government subsidies for green technologies and the transition to Net Zero.

There are some signs that the US policy is beginning to bear fruit. A manufacturing boom and productivity improvement contributing to higher GDP growth. Some have cast doubts on the sustainability of these trends but, for now, finance ministers around the world are looking on with envy.

Of course, much of this has been enabled by the sheer size of the American economy. However, it is simply impossible for medium-sized economies like the UK to compete on all fronts. They lack the economic clout of the US, China, and the EU, and state investment must therefore be more targeted. Idle talk about becoming a ‘world leader’ in strategic growth industries offers little clarity about which industries and how the critical investment will happen. Questions of fairness, income inequality, social mobility and ‘levelling up’ also colour the debate.

Industrial Strategy demands choices and trade-offs – and an honest appraisal of the country’s latent skills and economic potential

In its Economy 2030 report in December 2023, the UK’s Resolution Foundation called for “realism about trade-offs” and “clarity about context”. It said that a “hard-headed industrial strategy” would require “understanding the type of country we are and the opportunities and constraints this brings, without nostalgia about the past or wishful thinking about the future”. The Foundation advocated concentrating on the UK’s strength in broad-based services. A controversial stance, perhaps, but any future industrial strategy will need to be clear about where it believes the country’s strengths lie. This is, at least, a starting point for that level of discussion.

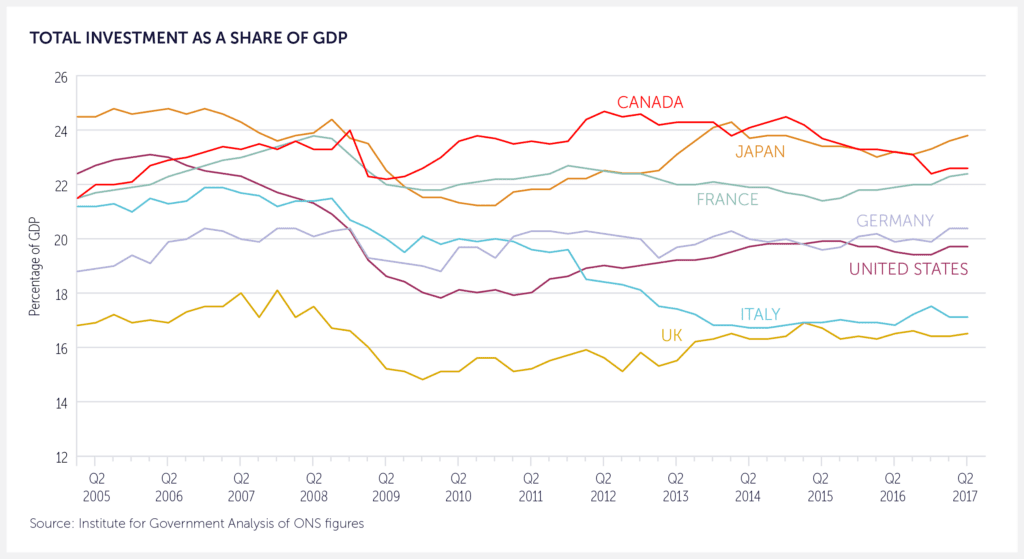

Where most commentators agree, because the data is so stark, is that the UK is starting from a point of chronic low investment. Capital investment fell in most advanced economies in the 15 years before the Covid pandemic but the UK was consistently bottom of the table.

The UK has also suffered from a lack of political focus. Even with the same party in power for thirteen years, there is a pattern of ripping up the work of your predecessor and starting again. The situation has been further complicated by the creation of four new or remodelled departments, each with some area of responsibility for Industrial Strategy. LSE’s Professor John Van Reenen has accused the government of “a policy ‘attention deficit disorder’ that has created massive uncertainty, sapping economic growth”. Already beset by chronic low productivity growth and decades of low investment, the UK can ill afford this lack of focus.

Despite movement during 2022 and 2023 in most of the world, by the end of this year, the UK seems no further forward. Helen Thomas, writing in the FT in November 2023, delivered a damning verdict.

“Think-tank IPPR reckons the UK has had 11 industrial strategies or growth plans in the 13 years since 2010. If anything, that seems generous – the 2017 industrial strategy, the last serious attempt at an overarching framework of priorities for the UK economy, was canned in 2021. The proliferation of often lightweight ‘strategies’ across government since then has been baffling – not least because of the lack of any obvious joined-up thinking or co-ordinating force behind them.”

While most business journalists, along with international organisations like the IMF, seem to have converted to the idea of Industrial Strategy, not everyone is convinced. In July 2023, The Economist devoted an entire section to dismissing the whole idea, using the term ‘Homeland Economics’ to describe the various Industrial Strategy initiatives around the world. It argued:

“Homeland economics will create billions of losers. Beneath the apparent reasonableness, there is a deep incoherence. It is based on an overly pessimistic reading of neoliberal globalisation, which in fact held great benefits for most of the world. The benefits of the new approach are at best uncertain. Meanwhile, attempts to break free economically from China are likely to be partial, at best. The benefits of green subsidies for the fight against climate change are also less clear than their proponents admit.”

The Economist’s argument runs over several articles. Giles Wilkes, has written a commentary on each one, agreeing with many of the points made in the critique while drawing the overall conclusion that the Economist’s stance was something of a lament for a lost world.

“You don’t have to believe – as the Economist accuses its antagonists of thinking – that globalisation of the 1990s and 2000s ‘failed’ for there to be a call for new policies now. I loved those decades but don’t think that the circumstances they existed in can be bottled up and re-released today. It is a huge challenge that productivity has stuttered since the gigantic event of the financial crisis, and some of this may be put down to a misconceived retreat from globalisation, but surely not most of it.”

It could be argued that the post-Berlin Wall Washington Consensus came to a political end in 2022, but that it had already reached its economic end by 2008. Stagnation has been a persistent feature of the advanced economies since the Financial Crisis. Waiting for a return to the 1990s, which is essentially what businesses and policymakers did during the 2010s, doesn’t appear to have done the trick. Add in the push for Net Zero, an ageing population, and a far less benign geopolitical system and we are clearly into a very different world now.

Even so, the UK still lacks a strategy that sends clear messages to potential investors. As Helen Thomas put it:

“The legacy of the churn of recent years is that businesses, quite reasonably, doubt the staying power of what is said today.”

Whoever wins the next election will find themselves having to take some strategic decisions about the direction of the UK economy and what sort of country a post-Brexit Britain wants to be. As other countries develop their strategies for meeting the challenges of the next decade, can the UK afford to be the only one assuming that, if we just leave things be and hang on for long enough, the good times of the 1990s will return?

It is likely, then, that Industrial Strategy will be a feature of all major economies in the coming years. Businesses will be subject to regulations, nudges, admonishments and (if they are lucky) subsidies. This is the background against which companies will need to plan for the rest of this decade.

UPCOMING CRF CONFERENCE:

UPCOMING PARC EVENT

Industrial Strategy in the 21st Century

Preparing Business for the New Economy

Thursday 22 February, London and Online