External Forces and Trends

Economic Outlook: Are We Prepared for a Low Growth World?

What are the implications of a low growth world? It’s not a subject that has had much discussion; although the advanced economies have endured 15 years of low GDP growth, government forecasters and economic commentators spent much of the period after the 2008 financial crisis assuming that there would be a return to the growth rates of the late 20th Century. After all, that had been what happened in the past. Recessions, even deep ones, were followed by a near-equivalent bounce-back, so the thinking and planning in most advanced economies simply returned to where it had been as if the pre-recession growth trend had continued.

Synchronised stagnation

This didn’t happen after 2008. No major advanced economy managed to sustain growth rates of even 2%. Many flatlined. By 2019, it was clear that low growth was set in. The Financial Times came up with the term ‘synchronised stagnation’ to describe the malaise. It was the same story after Covid. The ‘Roaring Twenties’ predicted by some commentators did not materialise. After a brief recovery, there was a return to the pattern of the 2010s. Even before the Russian invasion of Ukraine there were signs that any recovery was running out of steam. Both the OECD and the IMF have remarked on the slowdown and forecast continuing low growth into the middle of the decade.

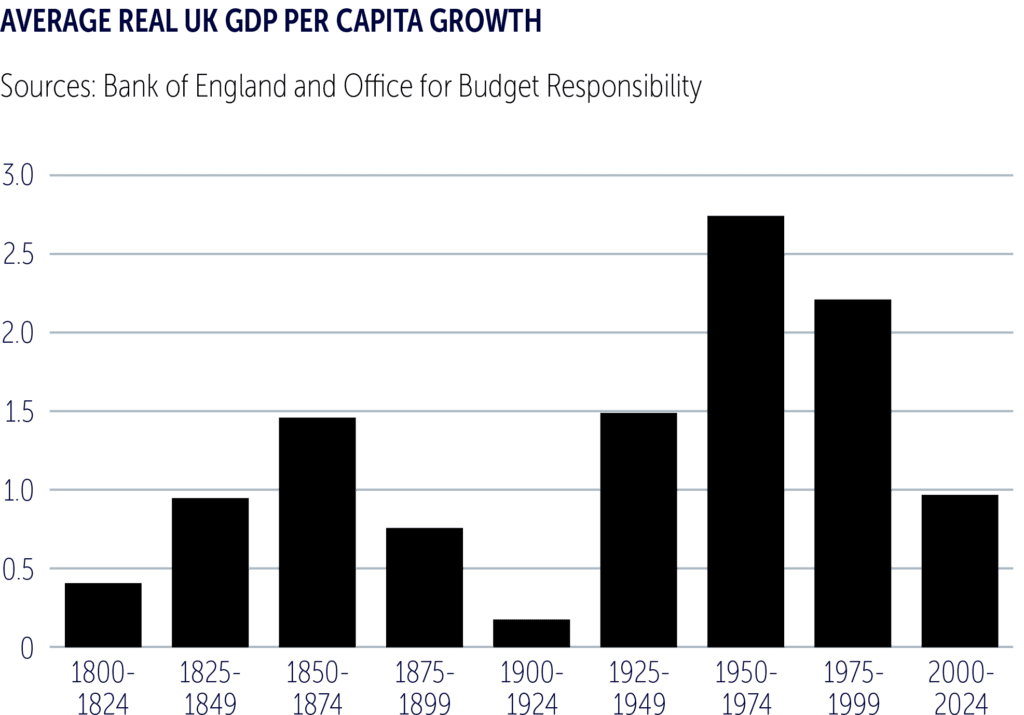

The Bank of England’s long-term economic data enable us to put the late twentieth century into its historical context. Economic growth barely existed until around 250 years ago when humans learnt how to use fossil fuels for industrial energy and mass production. Using the UK as an example, we can see that the second half of the twentieth century saw a rate of economic growth unprecedented even in the industrial era. It was an extraordinary period within an extraordinary period.

The quarter century since looks much more like those of the 19th Century. The gains of the early 2000s were wiped out by the financial crisis and growth has been sluggish ever since. The Covid pandemic made things that bit worse but, even without it, the numbers would still have been dire.

Tailwinds have become headwinds

For the advanced economies, the story since 2008 has been one of low productivity growth and consequently, low GDP growth. Some economists argue that the late twentieth century was a blip and what we are now seeing is a return to historically normal levels of economic growth. The high water mark of the postwar period was a product of the technological leaps during WW2, combining with pent up demand and a demographic sweet spot. A second boost came in the 1990s with what economist Charles Goodhart described as “the largest ever positive supply shock”, as China and the former Eastern Bloc countries brought an increase in workers, resources and markets into the world trade system.

But many of the factors that boosted growth in the past have now been thrown into reverse. As the UK’s Office for Budget Responsibility said, the tailwinds have now become headwinds.

“Fiscal tailwinds from a post-World War II baby boom, global economic integration, and easing of Cold War tensions have switched to headwinds in the first part of this century. Public finances are now under growing pressure from ageing populations, disappointing economic growth, a warming planet, and rising geopolitical tensions. Amidst these pressures, many governments have struggled to rebuild their fiscal resilience during the increasingly brief interludes between global crises.”

The headwinds are set to get stronger as populations age and environmental pressures intensify during the 2020s. Both factors make a leap in GDP growth much less likely. Shrinking working-age populations mean that there is less spare capacity in the economy. As Chris Dillow the former chief economist at Investors’ Chronicle put it:

“It’s not 2010 any more. There aren’t the unemployed real resources to permit a significant fiscal expansion.”

There is mounting evidence that global heating is hitting productivity. A Financial Times report in July 2023 noted that increased heat is disrupting economies and often stopping people from working. Factories, warehouses and transport infrastructure are not designed to operate in such high temperatures. Droughts, fires and floods are also taking a toll, diverting resources away from more productive activity.

Green growth is not a short-term fix…

Policy makers are hoping that climate change might offer an opportunity to boost GDP, due to the massive investment required for the transition to Net Zero. ‘Green growth’ might be a long time coming though. Almost all of our economic growth over the past 250 years has been based on fossil fuels. The transition to a carbon neutral economy implies doing the industrial revolution all over again.

Unlike previous industrial revolutions, the green transition will not enable us to go faster, build bigger and produce more. It will, at least at first, only enable us to do what we are already doing but without burning the planet. In time, reduced energy costs might lead to a productivity boost. Projections from the International Energy Agency, the European Commission and the UK’s climate Change Committee show break even points during the mid 2030s as operating costs fall and the investment starts to pay off.

The Resolution Foundation thinktank’s Economy 2030 Inquiry concluded that, while the Net Zero transition is clearly necessary, it cannot be relied upon to boost growth in the short-term.

“The net zero transition’s main macroeconomic effect in the short term is neither to significantly increase or reduce the level of GDP, but instead to change its composition. In the short term the transition is best seen as a significant invest-to-save process, as we pay in the coming years for the new infrastructure needed to allow us to heat our homes and travel without burning hydrocarbons. This will not be a major boost to growth in the short term because it involves replacing large parts of our capital stock rather than adding to it. In the longer term that infrastructure will be cheaper to run and if net zero-driven technological change leads to abundant, secure, and cheap electricity generation that would provide a major boost to growth. But an economic strategy cannot come down to counting on the latter materialising during the 2020s. Overall, net zero cannot be relied upon to deliver an economic silver bullet.”

…And neither is AI

Might Artificial Intelligence provide the productivity boost to return us to 2% per capita GDP growth? It’s possible but the so called ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’ has been promised for some time. Recent technological shifts have had little overall macroeconomic effect. Although we have seen the adoption of smartphones and mobile internet technology over the last 15 years, the impact on employment and productivity has been negligible. A report by McKinsey Global Institute warned that productivity gains from technology are by no means guaranteed and will require significant investment. It is difficult to predict the longer-term effects that AI might have but so far there is no evidence to suggest that a productivity big bang is a few months or even a few years away.

The implications of this sustained economic slowdown are significant:

- Our political and governmental systems were built during the postwar period of high growth. Government spending plans assume a certain level of economic growth without which tax revenues flatline, and borrowing increases. Over the coming decade, the rise in healthcare spending is forecast to outstrip economic growth in almost all advanced economies and many of the emerging ones too. The need to find resources to decarbonise economies will only add to the pressure, as both the skills and materials will be scarce and therefore expensive.

- Low growth means we are already having to adjust our assumptions about what we expect from the state, whether children are materially better off than their parents, at what age we retire, and how much help we are likely to get if we become ill.

- Lower economic growth also means that living standards will continue to stagnate. When the pie is growing, everybody gets a bigger slice. If the pie stops growing, arguments about distribution become more immediate. Public concern about inequality does not rise when inequality rises but when living standards stop rising. In a stagnating economy, outrage over corporate profits and executive pay is likely to intensify.

- Under such circumstances, increased state intervention is more likely as governments seek to find ways of securing their supplies, raising extra tax and controlling the direction of their economies. As Giles Wilkes points out in his piece on Industrial Strategy, governments will be forced to make tough choices. Politicians will put increasing pressure on business executives to invest and to ‘solve’ the low productivity problem. The level of intervention and direction will vary but, as Giles says, governments’ desire “to make work more productive and well-remunerated” is likely to see some significant interventions.

Our assumptions as business executives, consumers and citizens are still very much shaped by a world in which 2% per capita GDP growth was normal – and where we burned fossil fuels without a second thought. In the 2020s we are finally seeing the widespread realisation that these assumptions no longer hold.