External Forces and Trends

Trends in the Global Labour Market

PARC’s 2021 research report and event, Building a Future-Fit Workforce, looked at the forces shaping the economy and work over the next decade. In this article, one of our speakers summarises the impact of these forces and assesses the impact on labour markets over the next few years.

The outlook for global labour markets is unusually uncertain. Firms, in a widening range of sectors, are increasingly complaining of a labour shortage whilst advertised vacancies have hit new record highs in multiple countries. Yet hiring, in the US, Britain and much of Western Europe, is also rising at the fastest pace on record. And, for all the talk of a shortage of workers, unemployment remains above pre-pandemic levels, and employment rates lower, in most advanced economies.

Understanding the outlook means understanding that the global economy is in an unusual position. Demand has recovered much faster than supply as pandemic-related restrictions have been eased. That is pushing up prices and leading to a seemingly ever-changing carousel of different shortages. But demand has not just recovered but also changed its composition. Consumers, over the last 18 or so months, have spent more than is usual on goods and less on services. The typical advanced economy household bought more than is normal on Amazon and went to restaurants less. In response to changing patterns of demand, the supply side of the economy reshaped itself. Workers shifted away from hospitality and leisure focused activities towards sectors such as online retail.

On top of that shift came other changes. A move towards hybrid working has shifted the location of demand for many services away from city centres and towards suburbs and commuter towns. Travel restrictions have curtailed immigration. Many older workers in their sixties seem to have reassessed their engagement with work and decided to bring forward retirement.

In short, the labour market is out of balance. The supply of labour has been crimped by earlier than expected retirements and fewer migrants. There is a geographic mismatch between where available workers are and where the jobs are. And firms in the consumer-facing services sector have found that whilst they were closed by government fiat many of their previous staff found work elsewhere.

Amid this imbalance wages are beginning to rise. Headline wage growth figures, which are hitting two-decade highs in many advanced economies, need to be taken with more than the usual pinch of salt. The year-on-year comparison with 2020 when the economic fallout from COVID-19 was most apparent is artificially boosting the numbers in what statisticians call a base effect. That is not the only source of statistical noise. Low-paid workers were the most likely to lose their jobs over the course of the pandemic and so the remaining average wage was boosted by a so-called compositional effect.

Stripping out such impacts is not straightforward but suggests that the headline figures are less dramatic than they initially appear. Talk of a new era of radically improved worker bargaining power is almost certainly overstating what is going on.

The outlook for 2022 is cloudier than it appeared just a few months ago. Economic momentum has slowed amid shortages and faltering consumer confidence. Fiscal policy, which played an extremely supportive role throughout 2020 and early to mid-2021 is set to tighten in the US, Britain, and the Eurozone, while central banks are signalling higher interest rates ahead. Government support programmes – such as enhanced welfare payments and furlough-type schemes – are being scaled back or ended. As the current burst of hiring slows a small rise in unemployment seems likely. That extra slack in the jobs market should take some of the heat out of the building wage pressure.

Firms that are in desperate need of workers in the short term will have to pay for the privilege. Wage growth will remain high in late 2021 and early 2022 but as the months tick on reports of worker shortages, in most sectors, should subside. Global growth in 2022 will be more sluggish than in 2021 and so will global jobs markets.

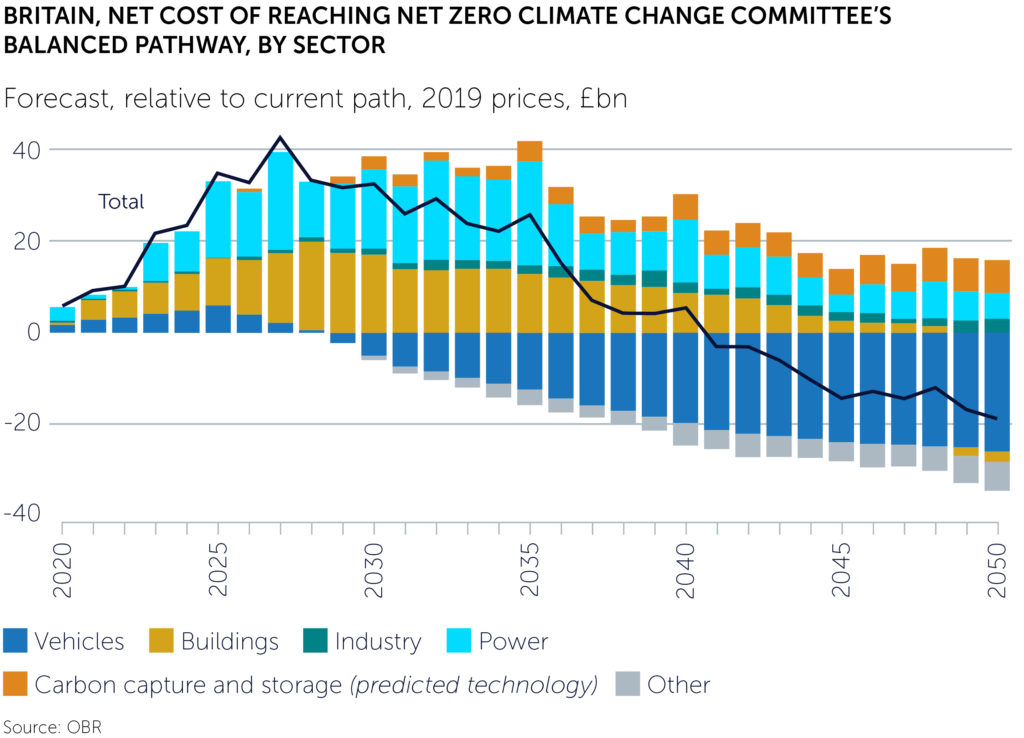

But if the current extreme imbalance in the labour market is beginning to right itself, 2022 will also be impacted by some longer running trends which have little to do with the pandemic and its immediate aftermath. The transition to Net Zero carbon emissions will require major shifts in the structure of global production. Few firms – even those far removed from areas like mining and manufacturing – will be unaffected. Governments are already setting out programmes to raise the price of carbon, to change transport and heating systems and new rules on environmental sustainability of buildings. Such regulatory and tax changes will challenge many business models. The need to decarbonise will add to economic churn throughout the 2020s. Equally important is a longer running demographic shift as workforces across the advanced economies continue to age. Whereas labour was relatively abundant in the 2010s, increasing retirements and lower migration will make it scarcer in the 2020s.

Even without the pandemic, the 2020s were set to be a decade of change which would have been challenging for many firms. The turmoil of 2020 and 2021 will likely be followed by a slower, but no less noticeable, period of transformation.

Firms which are just finding their feet again after the pandemic – and digesting the changes brought about by more hybrid working and tighter jobs markets – will have little time to rest. Decarbonisation and ageing demographics have both been widely discussed for at least a decade, but the 2020s are the decade in which both will begin to be keenly felt. Like the pandemic both trends will reshape economic demand and hence labour markets. While the elevated rate of wage growth seen in mid to late 2021 is unlikely to last, pay growth is unlikely to fall back to the historically very low rates of the 2010s. That may prompt a step change in capital spending as firms seek to control costs by automating more processes currently carried out by workers. That, in turn, could lead to even more labour market churn than is already expected.

The 2020s look set to be very different from the 2010s. An era of worker abundancy will be followed by one of relative scarcity. A period of relative continuity will be followed by one of change.

RECENT PARC MEETING:

Geopolitical and Global Trade Outlook

Catch up with the Post Meeting Notes

This article formed part of the HR Directors’ Briefing: Scanning the Horizon: Trends and Issues in 2022. View the full Briefing here.